Steve Schlam’s lifelong relationship with words began quietly, in the public libraries of Brooklyn, New York, where he was born and spent much of his childhood. That early immersion in stories is something he has carried with him while living in cities and small towns across the United States and in Mexico.

An actor as well as an author, Schlam has performed on stages everywhere he has put down roots, bringing the same attentiveness to language and character to both page and performance. He later earned a Master’s degree in Creative Writing and English, studying under Joseph Heller, the legendary author of Catch-22, whose influence helped sharpen Schlam’s narrative sensibility and comic precision.

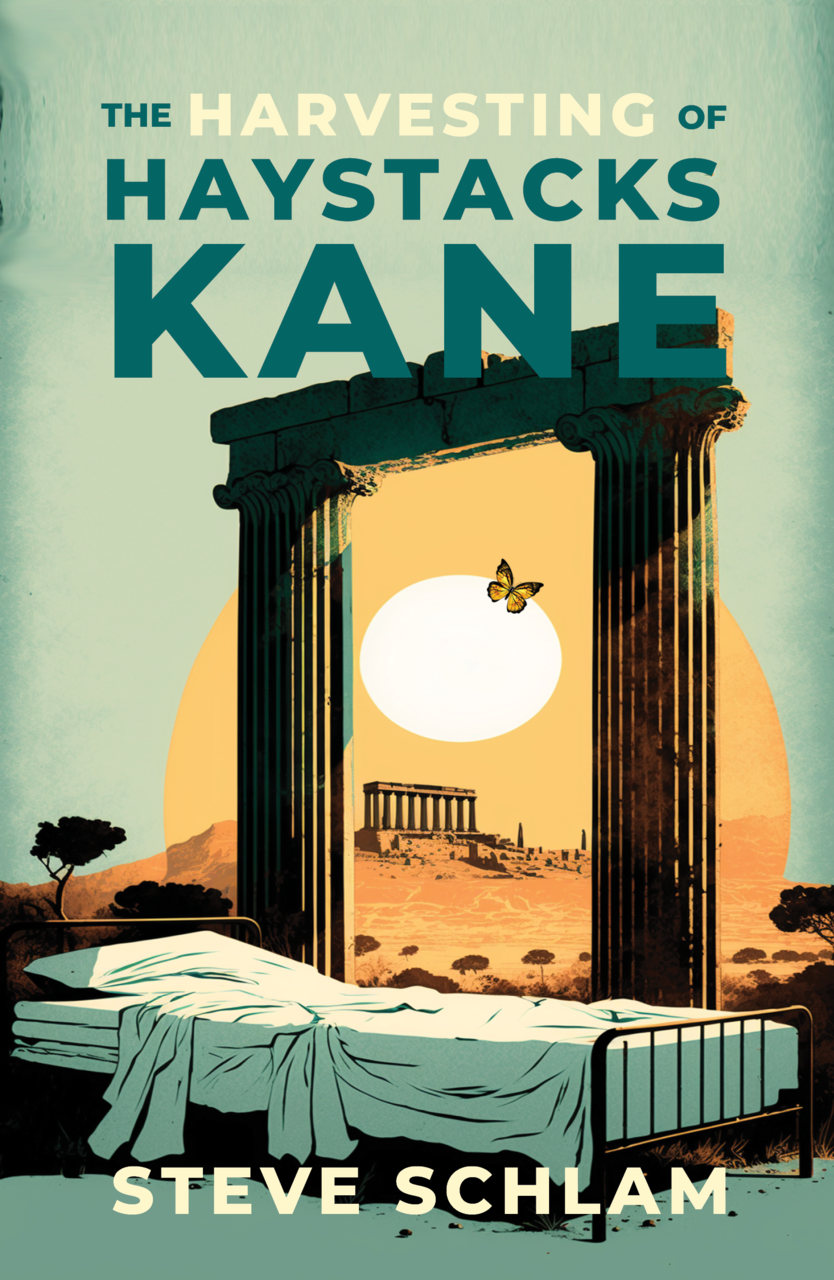

Those early library stacks, the stages he crossed, and the teachers who shaped him all converge in his novel. The Harvesting of Haystacks Kane follows a 607-pound professional wrestler (Herschel Kane) at the end of his life. Fading in and out of awareness from a hospital bed, he revisits the defining moments that shaped him. Career triumphs, personal failures, and the quiet ache of dreams left unfulfilled, including a lifelong wish to see a butterfly sanctuary in Greece. For Herschel, the butterfly symbolizes hope, redemption, transformation, and the possibility of escape from a life shaped by loss. The “sound of butterflies” becomes something even larger: a wordless, transcendent peace, the ineffable mystery he has been reaching toward all along.

Like his protagonist, the author is a Brooklyn native who lost both parents early in life, and the novel’s Brooklyn draws heavily from his own lived experience. Still, Haystacks is not a memoir: he is an only child, not a wrestler, and Herschel’s spiritual search for meaning and release is meant to reflect a universal human struggle rather than a personal one. With the release of The Harvesting of Haystacks Kane, Schlam sat down to talk about his path to writing, the influence of performance on his work, and the long journey from early library visits to his debut novel.

Can you tell us a bit about your journey as a writer, specifically how it began and how it carried through your life?

“You got a real good mouth on you, kid,” they used to tell me back in Brooklyn. “You got a way with words—you oughta be a lawyer.” Not a writer, you notice. A lawyer. Because I was a “nice Jewish boy,” and “nice Jewish boys” became professional men like doctors, accountants or lawyers.

So I became a lawyer. And hated it. I looked for a way out almost as soon as I’d gotten in. I practiced law on the civil side, and was a part-time lawyer for most of the ‘70’s into the mid-‘80s, when I jumped ship and left. I’d always read voraciously—two or three books a week when I was a kid—so soon after my life as a “professional man” commenced in earnest, I began to write. I quickly saw it as a lifeline: an antidote to the arid desert of the honorable practice of law and the straight world of getting and spending it embodied, and a ticket to somewhere better, somewhere that would nourish my soul if not necessarily my pocketbook.

It took me some time to get my bearings, but eventually I made my way into the newly minted MA program in Creative Writing at New York’s City College. I found myself in the world of serious literature: the poet Adrienne Rich, the novelist and founder of the literary journal Fiction, Mark Mirsky, and, of course, my teacher and mentor Joseph Heller, renowned author of Catch-22. I was in the company of fellow students, young and old, with something to say and the passion and determination to say it.

I wrote short stories while I studied. Joe always urged me to find a subject worthy of what he called my “high-toned, elevated” writing style and use it as a jumping-off point for a major novel. But I hadn’t found one by the time I completed the program, so I continued writing stories, waiting for Godot to arrive. Then, suddenly and without warning, the seeds that had been planted germinated and flowered. I had the most important dream of my life, and there before my eyes stood The Harvesting of Haystacks Kane.

How did that dream turn into the novel?

The first thing I remember is waking up to a flood of voices. At first, I was convinced I had toppled over the edge and landed in crazyville. But I soon realized the voices I was hearing were characters demanding to be heard.

I was living in New York at the time. Hot, tight, smelly New York in July: hazy, dripping with heat and humidity, and no A/C in sight. Once I realized what was happening, I bolted out of bed and sat at my military-surplus desk from the Army-Navy store, spending the next few hours sweating and trying my damndest to capture as many of those voices as I could before they dissolved into the heat and humidity.

I knew they represented the underpinnings of a novel, and I was immediately faced with a critical decision. Did I go back to bed for the few short hours remaining before morning and real life began, put on my suit, and march off to work as the unhappy, unfulfilled lawyer I was? Or did I kick over the traces of my comfortably bourgeois existence altogether and keep writing for as long as it took to satisfy all those clamouring, insistent voices—comfort and security be damned?

I wrestled with this while I worked. But in the end, I just didn’t have the courage to simply let it all go and forge ahead blindly into the forest of the unknown. I put down on paper as much as I could in a sort of frenzy and trudged off to work, bleary-eyed but knowing I was on the cusp of something: something important. A life change. Something BIG.

Haystacks is an incredibly complex character. With so much taking place in his mind, how did you go about refining your protagonist and his inner world?

I had an outline, an image of the main character, a general, if vague, sense of the narrative, and a somewhat murky shape of the whole. I quickly saw that Herschel, is a character on a journey to discover himself and understand what the world is all about and how it truly functions. I could see the raw clay of the novel begin to take shape as a classic bildungsroman, a novel tracing the moral and psychological growth of its young protagonist as he faces the challenges the world presents.

In the case of Herschel, however, the story would not move forward in time as we do with characters like Tom Jones or Tristram Shandy. Those stories follow the young hero as he encounters the world and learns from it. I realized that Herschel’s journey would unfold in reverse. We would travel backward in time alongside him as he sifted through his past to uncover the truth of what had happened and how it had shaped him.

So I had that much. From then on, I tried to resist the need to impose order and control. Instead, I kept the reins loose, gave the character his head, and let him lead me where he needed to go, revealing his heart and soul along the way. When I was successful, I was always rewarded: the words flowed and soared, streaming out of my arm as if they were writing themselves. When I was not, I struggled and sweated. I worked.

The novel plays with memory, identity, and the boundary between inner and outer worlds. How did you think about structure while you were writing it?

I had all these voices from the dream coming at me, demanding my attention. And there was a man of imposing presence filling up my imagination. The main character from the dream that had started it all, and who would reappear in the novel I began to picture taking shape from that raw material in that dream. I saw him both passive and in distress, immobilized and struggling, and recognized that his struggle was deadly serious, a life and death struggle if you will. But more than that, a struggle to discover and understand exactly what it was, the seemingly malign unseen force that appeared to govern the universe and had brought him to the state he now found himself in.

At the same time, I sensed that this force might also have a benign side, capable of releasing him from the bonds of his past and transporting him to the Eden he dreamed of: Greece, Rhodes, the Valley of the Butterflies known as Petaloudes, where he could finally live as his true self, in peace and tranquility, surrounded by “the sound of butterflies.” That part of his struggle seemed key, and it would require a journey into the past, through his memories, to sift and sort them into something coherent and meaningful.

And so I could see that that’s where all those other voices came in, they would be in dialogue with him, creating a point-counterpoint, a choral or contrapuntal structure in which Herschel’s ruminations and interior monologues alternated in a kind of call-and-response pattern with his memories. These voices, visitors who entered and left his hospital room (or perhaps only his disordered inner world) would guide, challenge, and illuminate him as he tried to make sense of it all. So there it was, I had the armature of the novel, and some of its beams and girders. Now all I had to do was write it.

The book’s language has been described as almost a character in its own right. How important was style and rhythm to your storytelling?

Critically important. I see language as lyric, music at its core, a pathway to transcendence, so first and foremost my writing aims to to transport my readers on a river of words to a place beyond their literal meanings, the place to which the best music and poetry take us. I was always mindful of William Faulkner, James Joyce, Thomas Wolfe, John Hawkes and other literary heroes and mentors all watching over my shoulder or gazing down from above, wherever they are or might be. Every word I wrote against that standard. I try not to analyze who I am as a writer and what I am trying to achieve because consciousness kills art. I am writing out of the oral tradition that began in pre-history when nothing was written and we told stories to one another in the dark. So I always read my work aloud before I commit to it fully, either to whomever I can commandeer to listen or to myself. Because if the story is done right, read right, its recital will mesmerize us like a chant or a prayer and carry us away. And that’s what I’m after.

In what ways has your acting background influenced the way you approach character and emotional truth on the page?

I dabbled in acting in high school, trained briefly in New York after law school, then set it aside until writing—and a nudge from my then-wife—pulled me back to the stage. For more than three decades, acting has balanced the solitary work of fiction, offering rare moments of complete immersion, when losing myself in a role felt like becoming most fully myself.

What has it meant to you to have your book published at this stage in your life, and what do you hope readers take away from it?

I feel vindicated. Proud. It was a long race. A marathon. And I crossed the finish line. I won. There is some sadness too, in the realization that the runway for the publication of future work is now shorter, but it still feels like a victory, not a valedictory, a last hurrah. Quite lovely, really.

As for what I hope readers will take away when they read it, I’d say two things: a meaningful journey on the river of my words to the place of transcendence I referred to before, and an experience of the “sound of butterflies,” the ineffable wonder we encounter during moments of peak experience that enables us to become one with all that is, to be. Now at long last. If I can achieve even one of those two goals, I will consider myself and my work a success. To achieve them both would be a triumph, and fill my heart.

📘 Get your copy of Steve Schlam’s The Harvesting of Haystacks Kane and explore more on his official website.